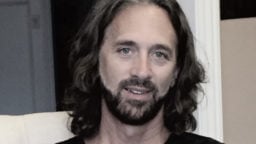

Scott Rodger’s roster is magic. No, really, it is.

After two decades as a stickler for the music biz, Rodger recently added illusionist and all-round WTF-producer David Blaine to his stellar Quest/ Maverick Management client base.

“I wanted to do something outside music this year,” the softly-spoken Scottish exec tells MBW, as we crown him as our latest Manager Of The Month. “I knew it would help keep me on top of my game.”

Rodger began his artist management journey in 1995 by marshalling the careers of Bjork and Sneaker Pimps, following a stint as a professional musician.

His relationship with Bjork would last until they parted amicably in 2011, Rodger having guided the Icelandic virtuoso to platinum success after she quit indie darlings The Sugarcubes.

Yet from day one, Quest was designed to be something far grander than a one-man operation.

Rodger always aspired to a professionalism and service that was a cut above your average management house – one steeped in the classy traditions of towering American music biz giants.

There is little argument that, 20 years on, he has achieved this goal in spades.

In addition to Blaine, Rodger’s personal roster at Quest now includes stadium rockers Arcade Fire and a true living legend, Sir Paul McCartney, with whom Rodger has been working for almost a decade.

Quest’s focus isn’t merely stuck in the rarefied world of superstar economics, either.

The firm has its fair share of artists teetering on the precipice of a global mainstream breakthrough, including Lykke Li and Mikky Ekko – the RCA-signed artist/producer who was propelled into the limelight not so long ago on Rihanna’s worldwide smash Stay.

Business-wise Rodger has backed up-and-coming management houses such as the UK’s Stack House (Rudimental, Gorgon City), Urock (Plan B, Jess Glynne, Tom Odell) and Scruffy Bird (Kodaline, Lianne La Havas).

Indeed, Quest is part of a bigger family itself.

Rodger’s firm, which boasts offices in London, New York and Los Angeles, became part of Irving Azoff’s Artist Nation at Live Nation before the legendary US mogul quit the firm in 2013.

These days, Quest is a key player in Live Nation’s Maverick management consortium – one of the more intriguing power bases developing at the very top of the entertainment industry.

At Maverick, Rodger is plugged into a persuasive network that includes the likes of Guy Oseary (U2, Madonna, Amy Schumer), Shawn Gee (The Roots, Jill Scott) Ron Laffitte (Pharrell Williams, One Republic, Alicia Keys), Clarence Spalding (Jason Aldean), Larry Rudolph (Miley Cyrus, Britney Spears) and Cortez Bryant & Gee Roberson (Nicki Minaj, Lil Wayne).

As MBW catches up with Rodger, he is knee-deep in an exciting new TV project; a pilot is due to be shot next month with Ben Stiller’s production company Red Hour.

(Rodger says the aim is to create a “punchy half hour of TV with one band doing three songs plus some comedy”, but he’s tight-lipped on a name.)

He makes enough time for us to ask him all about his career so far, his aspirations for Maverick and what the future holds – both for Quest, and the music business itself…

Sales. I was lucky, because the financial model was different than it is now, not necessarily better, but you could sell real volumes of records then.

I remember Bjork campaigns when we were doing 600,000 sales in France, 300,000 in Japan and Germany, 100,000 in Sweden. It added up to millions before you knew it.

It’s not like that anymore for many managers…

I know. These days, I look at Rudimental, managed by Henry Village (Stack House), who’s one of my partners and fantastic. They just had a No.1 album in the UK with 22,000 [week one] sales.

You can crack open the champagne and think: ‘Amazing for the band, we’ve got a No.1 album.’

“The music industry has to ask itself: how can we sustain a business on this basis?”

But so far it’s a challenging financial model – be it the marketing costs or the recording costs. That’s frustrating for us and our acts. And we’re only going to see a small percentage of the income from those sales.

The music industry has to ask itself: how can we sustain a business on that basis? How will artists get paid and actually continue their ability make music?

… and it’s therefore the same for managers.

I worry about young managers. Let’s say you’re 22 years old, you’ve got your first really cool act that everyone loves. You get that first record deal and that first publishing deal – maybe an £80,000 advance from both.

The manager gets his or her commission – £32,000, in total, off both advances.

“I worry about how young managers make the money work today.”

He’s thinking, ‘Great, a big payday.’ Then off comes his tax, his mobile bill – how’s he going to afford any assistance or an office for the next step?

It’s hard to make the money work today. I’m not talking about getting rich. I’m talking about just getting by.

The live thing is a bit of a myth unless you’re established.

If you’re a young manager with an [emerging] artist there isn’t much money in live. You lose money or break even at that stage.

You might get lucky with a big TV or movie sync or a commercial, that’s one way to get your deals recouped.

“The [idea live is very lucrative] is a bit of a myth unless you’re established.”

We’ve got an act, Lykke Li (pictured), who’s just finished her third album cycle. She’s never really sold masses of records yet we sustain a really healthy business.

Her live income is good but not huge, yet her publishing and label deals have recouped and she gets royalty cheques every six months. Why? Because her licensing business is massive.

She’s become very friendly with the sync community.

It might be a TV ad in Portugal for $50,000 or a brand partnership in France for half a million Euros. Before you know it, you’ve got an artist selling 150,000 albums worldwide but grossing serious revenue from the sync and licensing.

That won’t work for every act though – some of them will want to say no!

Case in point are Arcade Fire, who pretty much say no to everything. If you keep saying no, people stop asking.

They’re that rare kind of band who, if they say yes to something, give all the money to charity.

That’s what they did a couple of weeks ago with an LA Olympics 2024 ad – they wanted to use Wake Up and the band said they never license it.

In the end, the [ad people] offered to give a bunch of money to charity and the band said okay. That’s rare.

What did you find hard as a manager as Quest in the early days?

The hardest thing for any young manager is spinning the plates. You get your one act that consumes all of your time. Then that act might take some time off, maybe to write.

So you find your next act and start working, when your main act tells you they’re ready to go again. Can you divide your time between two acts? Can you prevent a fractured relationship if one act gets jealous of the other?

You start asking these questions… before act number three comes along.

“If you’re not careful as a young manager, your overhead can eat you alive.”

Before you know it you’re working 24 hours a day, seven days a week. You need to bring in other managers to help, and they have to be great, and the overhead starts to bite.

That was the toughest thing when I started.

I had six acts, and I was running a New York office for 12 years after Bjork moved there. A huge amount of investment went in.

If you’re not careful as a young manager growing a business like that, your overhead can eat you alive.

These days Quest, like a few of the other bigger management companies, has expertise in house that you’d traditionally expect to find at a label – especially when it comes to digital marketing. Why do you need a label these days?

The last roundtable with my management partners at Maverick was exactly that conversation. If a big act comes to us and says, ‘I don’t want to put this record through a label,’ can we do it?

The answer is yes we can. But then you’re faced with a multitude of issues.

You probably don’t need to fund the record as a big act will be able to fund their own recording. But where you spend the big money is marketing, and to do that properly and globally it takes millions of pounds.

Then the act’s got to do promotion – moving from Los Angeles to London, to New York, to Paris etc. etc. That all adds up.

If you’ve got a band and it’s five people, then they bring their friends and you’ve got to fly equipment around the world. It’s an expensive game.

“Let’s not completely write off the label’s contribution to a campaign…”

A manager can do all that stuff, it’s just a demanding part of the business.

There’s also still a physical business out there and no manager really wants to be dealing with picking, packing and shipping. It’s not a glamorous task.

The way to get around that is to push this stuff to companies who can take the weight off you. So, yes, we can do it without labels, but let’s not completely write off the label’s contribution.

The best labels out there today are fantastic at distribution, at getting the best from whatever physical market is left. They’re also really good at making sure your music is on every service available and being positioned properly.

They do also bring in some opportunities – although not that many in my experience. It all depends on the size and nature of the act and their agenda.

They’re a huge touring act who sell around 1.6m – 2m albums each time. We’re out of our deal, they have no deal, plus most of their catalogue has reverted back to them.

So they’ve got all the rights to their first mini-album, all the rights to Funeral and Neon Bible. The Suburbs comes back in the summer of 2017 and the next year we get back Reflektor.

We can do a futures deal; we can go to any label and sign the whole catalogue plus futures now. The question is, why would we?

“Arcade fire now have the rights to their first mini-album, funeral and neon bible. The suburbs comes back in 2017.”

I sat with the band the other week: they’re not bread-heads, they don’t care about [a big payday].

They have a couple of studios, so they don’t need studio time to make their next record. They’ll fund it themselves, which they’ve done for every album anyway. They just want to do what’s smart.

We can do physical with a boutique company and do some really nice vinyl. We can partner with a tech company. We can sign up to a digital aggregator. There are a lot of options.

Perhaps start with what you don’t want to do.

Well we’re not going to give anyone a cut of live or any ancillaries.

Are we really going to sign a deal that’s just going to give us a 25% royalty with packing deductions etc?

That’s not very exciting. Why would we ever do it?

Right. Why would we want to take 25% of streaming revenues?

We have deals for acts where they take between 60% and 90% of their digital revenues, including downloads.

This is the whole streaming myth: you read artists who say they don’t get paid from Spotify and Deezer.

“If you’re on 90% of every dollar, streaming is a very different ballgame.”

The reason they don’t? Well if you’re an artist who had one hit in 1972 that still sells today, unfortunately you probably signed your record deal in 1972, in perpetuity.

With packaging dedications, breakage and all the rest, before you know it that artist is on a gross of something like 7% of every dollar spent. They’re not getting paid because the money’s going elsewhere.

If you’re on 90% of every dollar [paid out], it’s a very different ballgame.

How do you get those deals?!

You only get them if you have an act who’s in a position to negotiate them, and/or owns the rights to their music.

That’s kind of what we do with Paul [McCartney]. He owns his entire catalogue so we do very limited distribution deals. Arcade Fire do the same as do other, smaller acts we look after.

The big problem now goes back to that 22-year-old manager trying to build a business; or his young band, who are working in coffee shops during the day to pay the rent, living off £10,000 – £12,000 a year just getting by.

A record company gets interested. They come in and say, ‘We’ll give you $50,000.’

“You can only get the best deals if you’re in a position to negotiate them.”

It’s kids in a candy store: ‘This money will let us give up our shitty jobs and let us focus on our band full-time.’

But what are they giving up for that $50,000? It might be a 15-20 year licence because the label’s reasonably friendly. That’s still 15-20 years of your life, gone.

Labels then want a cut of your live, a cut of your merch… but the band’s desperate and the managers inexperienced so they sign.

That band is then caught in a trap, not on a lot of money – maybe an 18% [streaming royalty] in the UK and 16% in the US and Europe. They’re caught. They’re done.

Will this ever change?

You know, the major labels do this research, and I’m one of the guys they come to when they employ these consulting groups.

You get asked: ‘Do you think we should be looking at doing more equitable digital deals?’

“The major labels are asking: should we be looking at doing more equitable digital deals?”

Maybe on physical they’ll keep the traditional royalty model – which, on paper, is [more understandable] because it’s a crappy business involving a lot of resource and risk.

But Digital is not the same. There may be a shift [for the majors] to do more equitable deals on streaming or downloads, but they don’t seem in a hurry.

Are you genuinely optimistic that will happen?

I think it will have to happen. Artists can’t survive out there.

I normally ask people in this feature what your advice would be to young managers. I’m guessing that’s part of it: don’t be knocked out by that initial deal.

Yes, and this: if a young act can find a way, any way, to record their first album themselves and pay for it, it makes a huge difference.

Home recording quality is great these days. Why not make a record yourselves? If you’re really that great, a producer might be willing to help you out.

At that point you own your rights and you can do smart licensing deals. As soon as you own your own rights, the game changes.

That’s what Arcade Fire did on their first record. It’s not the best-produced record they’ve ever done, but they cobbled it together and people love it.

They got a friend to do the art, spent very little money and had something they owned. And having ownership always means you’re going to get paid.

But it’s really hard when people are making you offers – especially if you want that Parlophone or Columbia logo on your vinyl.

Let’s talk about Sir Paul McCartney. He was quite late to Spotify but now seems to be an advocate of it.

He wasn’t that late to Spotify.

When you’re part of an institution like The Beatles it’s really tricky. Around the same time The Beatles went onto iTunes, which was a huge announcement, we began doing reissues with Paul – taking the gems from his solo catalogue, of which there are many, and doing ‘ultimate’ editions.

I’m really proud of that series; it’s the best series I’ve ever worked on and it’s won multiple Grammys. We’ve just done Tug Of War, which is phenomenal – the ninth in the series.

“Paul’s always been someone who’s embraced new technology and new formats.”

When we got to Ram [re-master in 2012] it was the fourth in the series, and the streaming question came up.

Older artists are always shot down by various media organisations for not being with the programme. Paul’s always been someone who’s embraced new technology and new formats.

So we started [putting his catalogue on streaming services] and it’s worked for us. It’s worked financially, creatively. It was the right thing to do.

Going back to your earlier point… it works financially because he owns the rights?

We share revenues with our partner. He’s got a smart deal. We’ve licensed the catalogue to Concord Music Group in the US, which is in turn distributed through Universal.

They’re the right partner for now, and we could base a deal on real-world modern streaming economics rather than legacy contracts.

How long have you been managing McCartney. And, sorry, but I have to ask: what’s it like to manage a Beatle?

I’ve been with Paul for nine years.

At the time I started working with him, I thought I would consult for the Memory Almost Full album and that would be that.

Which I’d have been happy with, don’t get me wrong – it’s such an honour to get to work with him full stop.

“I’d have been happy working on one album with Paul. It’s such an honour to get to work with him full stop.”

That rolled into a DVD collection, which in turn rolled into the Fireman project and then another album project.

One thing about me starting to work with Paul, looking at his operation at that point, I was the first external person he’d worked with since The Beatles.

It was important for me to remain an outsider rather than be folded into his MPL organisation.

To bring another perspective?

Exactly. It was good for me to work with other artists – I could see how the industry was evolving and what was relevant for other kinds of acts.

But being Paul’s manager is extra challenging, because you’re working with an artist who’s pretty much invented the rule-book and done everything you could ever imagine in music at every level.

I will say that MPL is a world-class organisation. No artist on the planet has a team like that around them. If I could put that organisation around every act I work with it would be a dream.

Ha, I remember it well: ‘I get bored quite easily.’

He’s the busiest guy I’ve ever met, between his live tours, music projects, film projects, book projects, art projects, soundtrack projects.

It just doesn’t stop – it’s insane. The biggest challenge is to keep up with him!

Working with Paul is like going to the best, most intense university in the world. I’ve learned more working with him than I could with probably any other act.

Can I ask about your X Factor experience – you took over the show for a short period, managing James Arthur and others, but you’ve since parted ways.

It was essentially a project we found for a manager friend of mine, Caroline Killoury, who I’d wanted to work with for ages.

Business-wise it didn’t make a huge amount of sense because the franchise itself got so big you were just a very small part in a huge machine.

I get on great with the people around it – the Syco team are great, a real pleasure to deal with. But in reality, you’re rolling the dice as to the artists you’re going to get.

The year we got the contract, it was the first time X Factor was open to any act with existing representation, which made it even more complicated.

The amount of work that went into servicing the X Factor account versus what we got back didn’t end up making much sense.

How do you mean?

We didn’t get any career artists out of it, which is what we were hoping for. There’s been a couple of career artists that have come out of TV reality shows, but they’re rare – Kelly Clarkson, maybe, or Carrie Underwood.

And then there’s One Direction. That’s a total one off. You’ll never find another One Direction.

“X Factor could run for another 30 years and I guarantee there’d never be another on direction. It’s a total one-off.”

X Factor could run for another 30 years and I guarantee there’d never be another One Direction.

That’s just the way the stars align.

We have the most amazing shared resources. When you get together with four or five really great managers, all of whom are incredibly successful in their own right with huge artists, it’s exciting.

The hope is that we can create some shared staff and resources. We have shared office space in Los Angeles and represent some of the biggest acts in every genre.

None of us know what the future music business model will be – but we’re trying to prepare for it. I’m the smallest manager in there…

Yeah, you’ve only got Sir Paul McCartney, Arcade Fire…

I know! But Guy Oseary is the most connected person on the planet – and the most plugged in to the tech space of anyone in music. No-one can touch him.

The aim for all of us is finding the best opportunities in the new world for our artists. Because with our leverage, with our artists’ joint social reach and live reach, the power – and I hate that word, but that’s what it is – creates the potential for some huge opportunities.

Are you still in touch with Irving? What impact did he have on Quest and your career?

Yes, I am, absolutely. In the couple of years I worked with Irving I found a great friend.

I learned a huge amount from him – not only deal-making but also how to do great things for your artists.

“I learned a huge amount from Irving Azoff. He’s probably the best manager that ever lived.”

He’s probably the best and most successful manager who ever lived. Again, I look at his work pace and schedule and it amazes me.

So much of my schooling has come in the past ten years. Look at who I’ve been able to learn from – Irving Azoff through to Paul McCartney, Michael Rapino, Guy Oseary, Ron Laffitte.

You can’t help but get better when you’re surrounded by guys like that.