The MBW Review is where we aim our microscope towards some of the music biz’s biggest recent goings-on. This time, we predict the next giant step for the great financialization of music rights in 2021. The MBW Review is supported by Instrumental.

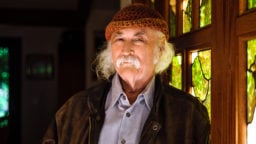

David Bowie. What a guy.

As well as all of his zeitgeist-shaping music – and clear-headed philosophical forecasts – Bowie was also something of a financial pioneer.

Working with David Pullman, Bowie famously launched the highly-innovative ‘Bowie bonds’ in 1997.

These saw rights to Bowie’s royalties in the US securitized into bonds.

In plain English, bonds act like loans, but with investors ‘lending’ a company / entity money rather than a bank.

Buying these bonds – so long as the underlying asset doesn’t default – offers these investors a way to get a guaranteed return from their investment, over a set period of years.

Bowie bonds, for example, offered a fixed annual return of 7.9%, over a period of 10 years, all based on the Thin White Duke’s royalties.

Why are we combing over history here?

Because MBW hears from multiple senior sources that ‘Bowie bonds’ – that is, bonds secured against music assets – are about to make a big comeback, with a transformational effect on the value of this industry.

Once again, it appears Mr Bowie was far ahead of the times.

What’s often assumed about Bowie bonds, seeing as they disappeared in 2007, is that they somehow failed. This is untrue.

As explained in the latest episode of MBW podcast Talking Trends, what actually happened is that the buyers who spent $55 million on Bowie’s bonds got their money back, plus their agreed rate of interest.

Bowie (because he was and remains, y’know, a genius) used the money these bond-buyers ‘lent’ him to re-acquire his own recordings catalog, which is probably now worth somewhere up to $1 billion.

So everyone was happy, right? Bowie, his bond-buying investors, and the financial community at large?

Not quite.

Things got wobbly, because the decade-long period during which the Bowie bonds matured (1997 to 2007) was… not exactly the most stable era in music industry’s history. *Waves at Napster and Limewire*

That wobbliness, in turn, had a problematic domino effect on Big Finance.

This is the critical part of this story – the key thing that’s changed from 2007 to now.

And it’s precisely why music-affiliated bonds, according to MBW’s high-up sources, are about to become one of the industry’s stories of 2021.

So… before a company offers investors / the market the opportunity to buy bonds, said bonds must be rated by one of a handful of venerable institutions.

These institutions, certainly in the US, are usually one of Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s, and Fitch.

What these firms are rating, ultimately, is the quality of the underlying asset / business behind the bonds. i.e. the thing that generates the money to pay investors their original money back (the principal), plus the agreed rate of interest.

Sometimes, bonds get good ratings, sometimes they get exceedingly good ratings, and sometimes they get very poor ratings… what you’ve no doubt heard to being referred to as “junk bonds”.

These ratings ultimately direct the level of investor confidence that each set of bonds attracts.

In the case of Bowie bonds, the underlying asset – i.e. Bowie’s music, and the money it was generating – suddenly looked rather vulnerable as the age of piracy crashed into the age of CD sales.

Initially, in 1997, the likes of Moody’s gave Bowie bonds an investment-grade rating; aka. platinum-plated, bet-the-house-on-it, super-solid stuff.

But then, as the whole music rights industry began to nosedive, things changed.

In 2004, Moody’s downgraded the Bowie bonds from an A3 rating to Baa3, a damning move which Investopedia calls “one notch above junk status”.

Bowie’s investors would have likely been panicking. And Wall Street would have been detecting a stink coming from music assets that wouldn’t wash off… ooh, for about 17 years.

Because today – as well you know, MBW readers – music assets are back in vogue in the Big Finance community.

Whether it’s Blackstone, KKR, Apollo Global Management or others, the status of music rights as an attractive “asset class” – an investment destination offering a high probability of return to investors – has never looked better.

That’s partly thanks to the stock market trailblazing of Hipgnosis Songs Fund et al, and largely thanks to streaming: not only does the revenue ‘pie’ of music grow every time the subscriber base of Spotify et al increases, but the predictability of music royalties has never been more robust.

Case in point: Back in the days of Bowie bonds, the financial performance of Mariah Carey’s All I Want For Christmas Is You – via CD and download sales – would have been far less predictable each year than it is today, when it rockets back up to the top of streaming charts every December (and rakes in millions of dollars).

That’s literally why Hipgnosis bought a stake in it.

Now we’ve covered the context… here, buried right at the bottom of proceedings, is the big news.

MBW’s sources tell us that at least one major music rights portfolio owner is currently seeking a handsome rating (perhaps a platinum-plated, bet-the-house-on-it, super-solid-stuff rating) for bonds securitized against music assets.

Yup: Bowie bonds are back!

Ultimately, if said bonds are rated well by the likes of Moody’s and then – crucially – perform at or beyond expectations for investors, it’s going to increase the value of music rights today very significantly.

As was said on the Talking Trends podcast last week: “Mark my words, we’re going to see a large financial entity buy a massive catalog of rights, then they’re going to split that catalog up into loads of bonds, and sell those bonds on to investors – and crucially, they’re going to be able to get a good rating for them.

“Don’t just watch these masses of billions pouring into the music industry right now to get a sense of the value of music rights, and how it’s going to keep on bouncing up and up.

“Just think of the genius of David Bowie – and understand that financial engineering could be the next big story in music, and make an already blossoming sector even richer.”