The following MBW blog comes from Music Business Worldwide‘s Associate Publisher, Dave Roberts.

There are radical new rules and trailblazing new routes in this newest of new eras in a new-look, new-feel music industry. Everywhere you gaze, box-fresh manifestos jostle for prominence in the post-revolution landscape.

It just isn’t like the old days anymore. You can’t release an album then sod off until the next one, expecting – haughtily certain, in fact – that your fans will wait and not get distracted or stolen, by Donovan, or the New Kids, or adulthood.

You have to keep feeding the fans. And no, it doesn’t have to be music, you silly old dinosaur; in some cases it’s hugely preferable that it isn’t; it can be your life, your opinion, your new hat, your new relationship.

You can’t be remote, your fans want to really know you. Fakery is out; image is dead. You must have an ‘authentic voice’ which, as soon as it’s assigned to you, you should use as often as possible.

Share. Share everything. Everywhere. When was the last time you posted?

“Pop stars aren’t pop stars anymore. They’re artists, or brands, or ‘CEOs of their own businesses’ – that’s a popular one.”

Quick, launch a podcast! DO NOT LOSE EYE CONTACT. (Unless you’re Adele, in which case do what you want. This sentence can be cut and pasted in random paragraphs throughout this column.)

In the background, meanwhile, record companies aren’t record companies anymore – they’re something else. Something less, or maybe more – no one seems able to agree. (The dividing line appears to be that managers think they’re something less, and the labels themselves think they’re something more.)

And pop stars aren’t pop stars anymore. They’re artists, or brands, or “CEOs of their own businesses” – that’s a popular one. Record companies only (humbly) exist to help said CEOs achieve their vision, and definitely not to make $1m an hour from streaming.

So, yes, this is all new, no one has ever done, thought or even imagined anything like this before.

Talking of unprecedented times… like most of you, I’m currently working from home. And after-working at home, drinking at home, eating at home and looking to various screens to fill my time at home. (Oh, and reading canonical novels, painting and learning Spanish – just like you, right?)

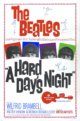

A couple of days ago, as a break from the box-sets, and part of a series of ‘comfort films’, I decided to watch A Hard Day’s Night. This of course, is the debut full length feature film starring The Beatles, released in the summer of 1964 just 18 months after their first number one.

It’s brilliant. You probably know that. But what’s interesting, 56 years after it was released, is that it is so 2020 (certainly as ‘2020’ as any film in black and white, co-starring Wilfred Bramble, can be).

A Hard Day’s Night was the Beatles’ label and their management reacting to genuinely unprecedented fan fever by saying, ‘You want to meet them? You want to know them? This is the best we can do: here they are – for you.’

(In the US, the band’s second album – the first on Capitol – was called Meet The Beatles; the title wasn’t plucked out of a hat.)

As well as being a great film by any measure in any era, to the modern music industry, Hard Day’s Night is an astonishing piece of ‘content’. The Can’t Buy Me Love sequence alone is basically 17 Instagram stories jammed together.

The Beatles are essentially being themselves, living their lives, but it’s in no way a documentary. They are versions of themselves, it is a version of their lives. They’re the Spice Beatles!

A Hard Day’s Night came with an accompanying album, the first featuring all Lennon & McCartney compositions. It was their third, and their third in 15 months. For good measure, they also released five EPs and eight singles between January 1963 and November 1964.

“Has any artist ever been more pitch-perfectly ‘always on’?”

And that was just the UK schedule: because of Capitol’s initial indifference to the group, there was even more music across a shorter duration in the US.

At the same time, The Beatles had launched the biggest fan club ever seen and, in 1963, made their first Christmas disc, a mixture of music, skits, messages and thanks, direct to fans. It was basically a podcast. And they would keep sending them every year until they split in 1969.

Add in the performance art press conferences, the ubiquitousness on pop radio, the crossover into traditional ‘variety’ territory…. the Beatles were inescapable, but also very much in control.

Has any artist ever been more pitch-perfectly ‘always on’?

There is nothing new under the sun, we are told in Ecclesiastes – but somebody had to write that in the first place, so, like much in the book it comes from, there’s some contradiction at play here.

It’s true that the modern music business, and the rate at which it’s evolving, is astonishing. It’s an exciting place to be and an exciting thing to write about.

And it’s natural that today’s artists and executives have one eye on their place in all this.

They, like all of us, welcome ideas of them “moving the needle” or “re-defining the industry” – and history may decide that that is precisely what they did in 2020.

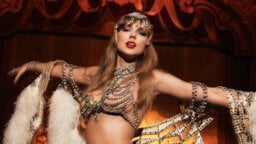

To pluck a couple of examples, maybe history will consider Taylor Swift’s shock move to record and release two acclaimed studio albums in the same six months of a (traumatic) calendar year; or maybe it will consider Lil Uzi Vert, who effectively released two chart-topping studio albums in two weeks back in March (Eternal Atake and Lil Uzi Vert vs The World 2, the first bundled with the second), just as COVID-19 began to surge (and terrify) in ‘the West’.

“Artists and executives, like all of us, welcome ideas of them ‘moving the needle’ or ‘re-defining the industry’ – and history may decide that that is precisely what they did in 2020.”

It should also be noted that the world probably doesn’t need another inherently Boomer-ish column saying, literally, ‘But what About The Beatles?!’

Yet sometimes, sorry, it really does have to be said. (Two years and two months between I Feel Fine and Strawberry Fields; George Harrison was just 25 at the farewell rooftop concert in 1969. These are astonishing sentences, mind-blowing facts).

This isn’t a criticism of undeniable progress, a debunking of modern methods, or an accusation of recycling.

But, when it comes to engaging with fans, creating narrative, letting the public see behind the curtain, filling the (tiny) gaps between albums, (not being hung-up on albums), making it visual, being real, becoming a brand, maybe the ‘new’ music industry isn’t completely new, yeah? Yeah yeah?Music Business Worldwide