The MBW Review offers our take on some of the music biz’s biggest recent goings-on. This time, as the industry heads to the Grammys, we ponder what the Billboard Power 100 is really for, and who benefits. The MBW Review is supported by FUGA.

The Billboard Power 100 is an ugly advertisement for the blockbuster music business’s worst insecurities and its most wretched vanity.

Discuss.

Only one portion of the above statement is directed at the annual list’s glaring lack of diversity, by the way – but considering how uneasy it’s making anyone with any kind of societal antennae, let’s get it out of the way, shall we?

Billboard unveiled its latest Power 100 on Thursday (Jan 25). It contained a chart showing that 17% of this year’s list is comprised of female executives – a rise on the 10% it counted in 2017.

Scratch beneath the surface, however, and this improvement is hardly worthy of congratulations; the upper echelon of the Power 100 is every morsel as white and male as it’s always been.

Just 12% of the list’s Top 50 is made up of women. In the Top 25, that number falls to one in ten, with a solitary solo spot for a woman – UMPG boss Jody Gerson at No.8. (Gerson is the first ever female executive to be granted her own Top 10 position.)

Other barometers of diversity are similarly deflating.

In a nutshell: it’s 2018, and while the music business keenly banks its chips on urban music, swathes of the Billboard Power 100 carry such a blinding level of whiteness, Colgate would pay millions to patent it.

Only one black executive is deemed powerful enough to earn a solo place in the top 25: Warner/Chappell chief Jon Platt, at No.11. (Apple Music‘s Larry Jackson does appear at No.7, but as part of a corporate group of four alongside Robert Kondrk, Eddy Cue and David Dorn.)

It would take you all the way to position 27 to find a non-white female – Epic Records head Sylvia Rhone, who has presided over a golden period for the Sony label following the departure of L.A Reid last spring.

When you visit this year’s Power 100 online, you’re presented with a straight-up textual list of the entrants.

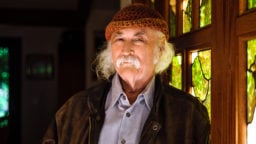

If you’re wondering why Billboard has ditched the headshot picture parade of years gone by, it’s probably because it looked like this:

Billboard would no doubt argue that the rankings simply reflect a sad lack of diversity in the rarified echelons of the music business. And maybe, actually, that’s a fair rationalization.

The problem, for anyone who cares about the future health of the industry, is that’s not really the point.

The mechanisms behind the Power 100’s generation are immaterial – it’s the potentially damaging effect it has once it’s in the wild that matters.

Namely: what demotivating impression does the Power 100 offer, year after year after year, to talented young entrepreneurs who happen not to be white and/or male?

And yet. The discomfortingly same-y make-up of the Power 100’s finalist pool isn’t actually my biggest problem with it.

That would be its bizarre, Faustian focus on that grubby little word: power.

This isn’t a list about what you’ve contributed, it screams – this is a list about what you control.

And in the current industry climate, that not only seems a little tone deaf, it seems a little dumb.

Power in the music business, in any business, is, by its very nature, finite.

The danger of hero-worshipping the ‘power’ of music executives is, therefore, that you suck even an iota of career-boosting status away from those who channel deific-level confidence to push themselves, and the industry, forward. Aka: the talent.

For an exec to steal a hit of that egotist opioid, even momentarily, is to grapple with their own industry’s golden goose.

If you don’t buy the idea that artists notice or care about the industry hoopla surrounding Billboard’s annual contest, I suggest you start listening to Demi Lovato.

In 2015, Lovato took to Instagram to offer impromptu praise of her long-term manager, Phil McIntyre. She wrote: “So many other managers try to become the artists themselves by putting their name out there just as much as their artist by doing interviews or photoshoots.

“But Phil is one of the most HUMBLE and hard working people I know… I’m SO GRATEFUL FOR YOU!!!”

Public, unrestricted gratitude from a blockbuster artist – who notices and appreciates that an executive is actively declining to bask unedifyingly in her limelight.

Shouldn’t testimonials like this, whether private or otherwise, be the only indications of music industry ‘power’ that ever matters?

The importance of this stuff becomes a little more serious when you check the data.

Look very carefully at the below graph, based on some MBW number-crunching. It shows the annual FY recorded music revenues and ‘A&R costs’ at Warner‘s worldwide labels in recent years.

‘A&R costs’ in this context represents the company’s expenditure on music-making – here’s the essential bit – combined with its royalty payments to artists.

In FY2017, as a percentage of total revenues, Warner labels’ A&R cost hit 32%.

This was unusual; over the previous decade, it never once rose above 30%.

What this indicates: as major music companies return to record-setting growth, margins negotiated and earned by artists – and therefore sacrificed by labels – are steadily growing.

This certainly isn’t unique to Warner: all large-size, copyright-acquiring music companies are learning to deal with ever-greater contractual demands from frontline artists and songwriters.

Last May, Sony Music COO Kevin Kelleher was asked by investors in Japan if escalating artist royalty percentages could impact the company’s profitability. He acknowledged: “With respect to the shift towards streaming, there are higher talent costs, so we’ve got that [margin] pressure.”

In other words, as labels increasingly have to do less donkey work for artists, so the artists are inevitably demanding – and receiving – a greater slice of the pie.

“With respect to the shift towards streaming, there are higher talent costs, so we’ve got that [margin] pressure.”

Kevin Kelleher, Sony Music (speaking in May 2017)

The stats don’t lie: if you want to talk about ‘power’ in the 2018 music business, only an idiot would be satisfied to keep artists out of the conversation.

This trend is only getting more pronounced.

Emboldened artists are now reportedly demanding that majors enter joint ventures that are 60/40 in favour of the performer – something which would have been unheard of even a few years ago.

Further food for thought: According to Nielsen, just three artists – Drake, Kendrick Lamar and Ed Sheeran – were jointly responsible for nearly 3% of all audio streams in the US last year (11.7bn plays out of a 400.4bn industry total).

Three percent was a bigger market share than that claimed by the likes of Island, Disney or Big Machine.

All three of these artists were conspicuously absent from Billboard’s Power 100, of course – where industry ‘power’ exists in a vacuum exclusionary of the people who actually sell the tickets and who actually convince people to pay for Spotify.

Now, some other media and event platforms celebrate and recognise music industry excellence – ie. the achievements and milestones of the music business’s cleverest minds in a given year.

I have no issue with this. The receipt of recognition of your professional pursuits is a primordial craving. It can drive individuals on to greater heights; it can buttress daring and creative thinking; it can help build a better business.

The key difference here is that the Billboard Power 100 is overtly not fixated on excellence, it is fixated on influence: who is making the biggest bets, who is turning the most heads at Soho House; who is king of the fucking jungle.

Unfortunately, the consequences of this chest-beating, shaft-waving nonsense don’t stop at a few figurative piss stains up the wall.

The Billboard Power 100 puffs out an uncomfortable cloud of tension into this business at a sensitive juncture – when it’s becoming crystal clear that the music industry orbits like never before around its artists, and not the other way around.

For further evidence, just pick up Billboard’s Power 100 issue – out now – and read the cover feature with Eminem and his long-term manager (and new boss of Def Jam), Paul Rosenberg.

Rosenberg, No.25 on Billboard’s list, is mid-photoshoot when his megastar client begins ribbing him for his new-found media rock star treatment.

“Yo, Paul! Can you sign a CD for me when you’re done?” calls out Marshall Mathers, with a clearly pointed gag. “You’ve got the streets on fire right now!”

Later in the interview, Eminem pokes his manager yet again. He jokes: “Don’t forget the little people on your way up to the top.”

Rosenberg rejoinders this wind-up smartly, and in good humor: “You’ll always be the little guy to me.”

This line works precisely because it pricks the unspoken, ludicrous concept: that a background executive could ever claim to wear the real trousers in the modern music business.

Right now, in a fast-changing industry, the earnest back-slapping of Billboard’s Power 100 feels tired, outmoded and poorly timed – as performers increasingly scrutinize the true value of their commercial partners.

The notion that ‘power’ in the music industry can exist exclusive of artists is not only undignified and ungrateful – it’s preposterous.

The Billboard Power 100 was born in 2012 (back at a time when – eeeeeesh – the magazine put one female executive in its entire Top 50).

It might be recent history, but back then, the music business was damaged, uncertain and contracting.

Perhaps its top executives needed a vestige of self-congratulation to remind them that, even as all the numbers tumbled in the wrong direction, their professional arsenal wasn’t without merit.

Well, times have changed.

Today’s music business is a new and exciting industrious playground, where the onus is entirely on corporate partners to constantly prove their value to star creators.

After a long period in the wilderness, it is an industry finally returning to strength.

All power, quite literally, to the artists that have made it happen.

As for the rest of you? Sit down, be humble.