Make no mistake, the album is fighting for its life.

Sales of music’s most beloved format are in free fall in the United States this year. According to figures published by the RIAA (Recording Industry Association of America), the value of total stateside album sales in the first half of 2018 (across download, CD and vinyl) plummeted by 25.8% when compared with the first half of 2017.

If that percentage decline holds for the full year, and there’s every indication it will, annual U.S. album sales in 2018 will end up at half the size of what they were as recently as 2015. To put it more plainly, U.S. consumers will spend around half a billion dollars less on albums this year than they did in 2017.

The CD album is, predictably, bearing the brunt of this damage. After a comfortable 6.5% drop in sales in 2017, in the first half of 2018, revenues generated by the CD album in the USA were slashed nearly in half – down 41.5%, to $246 million.

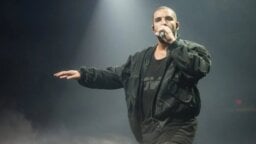

It’s not hard to see why. 2018 will go down as a landmark year for the acceleration of the decline in physical album sales: The likes of Drake, Eminem, Cardi B, Travis Scott, Migos and Kanye West have all released hotly-anticipated new LPs exclusively on digital services in their first week. All brought physical formats into play only after their records’ initial “sales” rush was over.

Hip-hop’s biggest names, it seems, are actively turning their back on the CD (and on brick-and-mortar retailers) — instead focusing on the likes of Spotify and Apple Music, where their genre is currently the king of kings.

None of this, of course, is a big shock.

Back in 2014, you may remember, Spotify co-founder Daniel Ek had an awkward public sparring match with Taylor Swift, following the superstar’s decision to pull her back catalog from his service. Facing down accusations that Spotify was “cannibalizing” the album, Ek wrote, “In the old days, multiple artists sold multiple millions [of albums] every year. That just doesn’t happen anymore; people’s listening habits have changed — and they’re not going to change back.”

He wasn’t wrong. As we all know, the music business held hands with Ek and dived profit-first into a streaming-led industry.

Now, however, a murmur is quietly breaking out: In the rush to follow the money, did the music business sacrifice something more valuable than it could have realized?

Sure, hits on streaming services make a lot of people a lot of money. But as the death knell rings for the album — and the music industry returns to the pre-Beatles era of track-led consumption — are fans being encouraged to develop a less-committed relationship with new artists?

The answer to that question ultimately depends on how those fans are consuming music on Spotify, Apple Music, et. al. One thing’s for sure: Not all new music is created equal — and the stats bear it out.

Take Drake’s Scorpion, the biggest album in the U.S. market this year. In a clear bid to rack up as many streams possible (and break multiple records in the process), Scorpion is 25 tracks long. Yet, according to numbers I’ve obtained and crunched from Spotify-monitoring site Kworb, some 63 percent of global streams from Scorpion on Spotify since the album’s release in June have come from just three songs: “God’s Plan,” “In My Feelings” and “Nice for What.”

In fact, just six songs on the album (also including “Nonstop,” “Don’t Matter to Me” and “I’m Upset”) have claimed 82 percent of its total streams. The other 19 tracks get just 18 percent of the spoils between them — an average of less than 1 percent each.

It’s a similar story with the biggest album of the first half of the year in the U.S.: Post Malone’s beerbongs & bentleys, from which just three tracks (“Rockstar,” “Psycho” and “Better Now”) account for 62 percent of worldwide Spotify streams.

You could argue that things have always been this way — that fans in previous eras would buy albums and then simply rinse and repeat their favorite individual tracks, ignoring what they deemed to be duds.

Additionally, you could argue that streaming has been wonderful news for the album — any fan anywhere in the world can now legally consume albums for “free” via Spotify, rather than shelling out a potentially prohibitive expense on CDs or downloads. If the experience of listening to full albums was compelling enough in 2018, therefore, the format should be thriving.

Yet industry machinery has certainly propagated this dismantling of the LP. The Billboard 200, still the most recognized album chart in the world, has, since December 2014, bundled together streams of individual tracks from an LP as “streaming-equivalent albums.” Billboard’s current, much-debated formula: 1,250 paid-for streams from the likes of Apple Music or Spotify Premium count as one album “sale”, as do 3,750 streams from ad-funded services like YouTube or Spotify’s free tier.

This has led to some pretty odd situations: Drake’s Scorpion, for instance, sold 160,000 true album units (via download sites) in its opening week, but, according to Billboard/Nielsen, more than three times this amount (551,000) came via “streaming-equivalent albums.”

In Scorpion’s second week on the Billboard 200, the potential silliness of “streaming-equivalent albums” came home to roost: The album sold (as in actually sold) just 29,000 copies on iTunes, etc., yet nearly 10 times this “sales” volume (288,000) was cobbled together from single-track streams.

The music industry is facing a bit of an existential crisis, then: How can something (streaming) be considered the “equivalent” of something else (an album sale) when, by your own measure, the former now completely dominates the latter?

In 2018, “streaming-equivalent albums” seems like daft phrasing. It is e-mail-equivalent faxes. It is car-equivalent steeds. It is Netflix-equivalent Betamax.

The death of the album track, if not the album itself, is having a significant commercial impact.

Lucas Keller is the founder of Milk & Honey in Los Angeles, a management firm that looks after some of the hottest behind-the-scenes pop songwriters and producers in the modern marketplace. He told Music Business Worldwide last week that the days of his clients making any real money from non-hit album tracks are now “pretty much over.” Keller commented, “I sit at a dashboard . . . showing the publishing revenue across the board on all of my clients, and I have a really good idea what Track 9 isn’t worth.”

The music industry is waking up to this fact, and it’s keen to to arrest the devastation. On Saturday, October 13th, the U.K. music business clubbed together to launch a nationwide campaign: National Album Day.

This was a big deal. The major labels (via the BPI), the independent labels (via AIM), the Official Charts Company and a vast network of U.K. music retailers joined forces to push their crusade to the public. It got wall-to-wall coverage on the radio channels of the BBC — another key partner.

The idea was to ape some of the magic of Record Store Day, the annual initiative that sees a yearly surge in physical music-buying on both sides of the Atlantic. Can you guess what happened?

Despite everyone’s best efforts, U.K. album sales fell slightly in the week of National Album Day.

As predicted by Daniel Ek four years ago, the public is obviously growing increasingly comfortable with its playlist-driven, track-led music-consumption habits. The music industry, however, is starting to question whether it’s quite so sure.