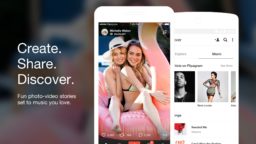

Flipagram is a social video and photo editing platform that boasts in excess of 30m unique users.

The services allows its audience to create ‘short stories’ using photos or videos set to music.

Flipagram’s pitch versus other social platforms is that its videos ‘offer more narrative space than Vine or Instagram looping videos, but are shorter and less cumbersome to create and share than longer length YouTube or Facebook videos’.

Last summer, Flipagram announced that it had obtained set of music licences in its home market of the US, which permitted it to use song previews of 40 million tracks.

It secured agreements with the three major labels plus top publishers, as well as indie label body Merlin and independent artist distribution platform The Orchard.

As such, Flipagram is now seen a friend of the music business. It even runs its own music chart.

On the surface, it’s exactly the sort of tech startup that brings optimism to music rights-holders about the future, especially now one of the biggest copyright infringers out there – SoundCloud – has begun its entrance into the world of legal, licensed services.

Yet a new interview with Flipagram’s CEO, Farhad Mohit, reminds the music industry how far it has to go before music-using startups habitually play ball from day one.

“We did it like entrepreneurs do sometimes – We did it and decided we’d ask for permission after.”

Farhad Mohit, Flipagram

After Mohit indicates that music “plays such an important role in the tonality and emotional leverage” of the sort of mini-movies Flipagram users create, Re/Code asks him whether he ‘went out and struck deals’ with record labels in the platform’s early days.

He replies: “We did it kind of like entrepreneurs do sometimes, we kind of just did it and [decided] we’d ask for permission after.”

That’s just how entrepreneurs do it sometimes.

One assumes Flipagram paid its electric bills in those early days. And its server costs. And its programmers.

You see the point.

So how much longer did artists and songwriters have to wait until Mohit’s team went legit and started paying them for use of their music?

“It took a good year and a quarter or so from the first outreach and the first set of deals coming in,” admits the exec.

“It’s a very complicated rights environment that’s been created in music copyright. Suffice to say I had a pretty good education in music rights management by the end of it.”

‘Tech startup blames music rights complication for not bothering to get an initial licence’ is no great surprise headline.

But in this case, it’s a useful reminder for the music industry not to kid itself into thinking that this type of corporate runaround is becoming a thing of the past.

“We’ve secured the rights to these previews with separate agreements with each of the labels that compensate them for their rights and their artist’s rights,” adds Mohit, who reveals that approximately five million Flipagrams have now been created using One Direction’s ‘Story Of My Life’.

In addition, Flipagram gets paid affiliate fees when its users head directly to iTunes to buy a track they hear on its service – a strategy it hopes to extend to other e-commerce platforms like Airbnb.Music Business Worldwide